The AI gold rush has given rise to a new breed of prospector, self-anointed ‘AI experts’ who are well aware that expertise can be manufactured, performed and, most importantly, monetised.

These self-styled experts boldly offer their insights into generative AI, yet many lack even basic credentials or practical experience in machine learning, natural language processing, or large language models.

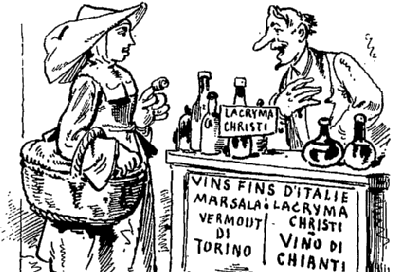

The parallels between AI gurus and the miracle cure salesmen of the late nineteenth century are more than superficial. Both phenomena emerged during periods of rapid technological change that outpaced public understanding. Both exploited the gap between scientific possibility and popular comprehension. And both relied on theatrics. AI gurus are often very polished speakers, very presentable and trustworthy in demeanour.

But where the original snake oil salesmen were constrained by geography and the physical limitations of travelling shows, today’s AI gurus leverage algorithmic amplification and network effects. A single LinkedIn post proclaiming ‘Ten AI Trends That Will Transform Your Business’ can reach millions, each share adding a patina of credibility through social proof.

Understanding this phenomenon requires examining the systemic incentives that enable it. The panic around the current AI boom has created an enormous demand for guidance, demand which far exceeds the supply of genuine experts who have spent years understanding the mathematical foundations of machine learning or the nuanced challenges of language modelling.

Into this gap rush the gurus, the interpreters, the simplifiers, those who can package complexity into a digestible narrative (for a consult fee, of course). The democratisation of ‘expertise’ through social media has created a curious inversion where visibility often trumps veracity, where the ability to craft compelling narratives about AI supersedes actual understanding of gradient descent or attention mechanisms.

There are tells, of course, the most glaring of which is the moniker itself, ‘AI expert’. The catch-all term ‘AI’ is incredibly vague, and genuine specialists typically specify their domain, whether that’s machine learning, natural language processing, computational linguistics, or some other specialisation. The vaguer the title, the greater the caution should be. Real expertise often carries nuanced distinctions that reflect significant professional experience within a specific aspect of artificial intelligence.

But imprecision serves a strategic purpose for gurus: by avoiding specificity, they can maintain flexibility in their pronouncements, pivoting seamlessly between discussing chatbot ethics one moment and pontificating on artificial general intelligence the next (basically, following the opportunity). Their expertise is performative rather than substantive, existing primarily in the space between public anxiety and technological complexity, that liminal zone where authority can be asserted without verification.

The genuine expert speaks with increasing precision as questions become more specific; the guru speaks with increasing vagueness. Ask about transformer architectures, and watch whether the response includes technical details or retreats into metaphor. The researcher acknowledges limitations and uncertainties; the guru promises revolutionary transformation. And of course, the specialist has published peer-reviewed papers and books with reputable publishers (not self-published through Amazon CreateSpace) and contributed to scientific projects funded by public research bodies; whereas the generalist has published thought leadership pieces and delivered lots of speeches at corporate events and tradeshows.

The real problem with the AI guru is that its consequences extend beyond individual opportunism to shape public discourse about artificial intelligence in profound ways. When ‘thought leaders’ without appropriate research grounding dominate conversations about AI governance, AI ethics, or AI’s societal impact, the resulting frameworks often lack the nuanced understanding necessary for effective policy or practice.

The proliferation of synthetic expertise creates a form of epistemic pollution, confident pronouncements about AI’s capabilities and limitations that bear little relationship to technical reality. This shapes public expectations, influences investment decisions, and informs regulatory approaches, often in ways that neither advance the technology nor protect society from its genuine risks.

The solution is not gatekeeping or credentialism for its own sake, but rather developing better mechanisms for evaluating and contextualising claims about artificial intelligence. This requires both individual and institutional responses: readers must become more sophisticated consumers of AI discourse, while platforms and publications must develop better methods for vetting expertise.

The current moment demands what might be termed ‘epistemic hygiene’, a careful attention to the sources and structures of knowledge claims about artificial intelligence. This doesn’t require dismissal of all popular communication about AI, but rather distinguishing between legitimate translation of complex ideas and the manufacture of false authority.

The AI guru phenomenon embodies a central paradox of our information age: the democratisation of access to platforms has not democratised expertise itself. Instead, it has created new forms of information asymmetry, where those most visible are not necessarily those most knowledgeable.

As artificial intelligence, particularly generative AI, continues its trajectory to critical infrastructure, the stakes of this confusion grow ever higher. The challenge is not just to identify the snake oil salesmen of the digital age, but to understand the conditions that create and sustain them. Only by recognising the systemic nature of synthetic expertise can we hope to cultivate more authentic and productive dialogues about one of the most transformative technologies of our time.

The merchants of digital promise will always exist at the frontier of new technologies. Our task is to ensure that their theatrical certainties do not drown out the careful uncertainties of those actually building the future they claim to predict.